Case Studies: Marketing Authorization & post-approval

A failing Patient Support Program

Project brief

A company launches a patient support program. The program fails due to lack of patient interest in registering for the program and limited support by physicians. The case study gives details on the process and reflects on the reasons for the failure of the program.

Situation

A company aims to launch a new medical drug treatment for a chronic disease. During regulatory submission they develop a patient support program to help with treatment adherence. The assumption is that patients who best understand their disease and how the new medical drug should be applied, will experience highest benefits from the drug treatment and better cope with potential side effects.

Challenge

How to design a patient support program that really addresses patient relevant needs and thus supports by resolving problems appropriately? How to communicate and disseminate information about the program and trigger interest among eligible patients?

Objective

The objective is to offer patients a support program right from first availability of the new drug treatment in order to enhance correct dosing and application of the drug. Also, the program shall give patients the opportunity to ask questions during treatment and provide feedback about their experience with it. Final goal is to support treatment adherence.

Procedure

Approach

The company designs a program educating about the disease and the treatment. The content shall be provided primarily via telephone trainings accompanied by printed materials and a password-protected online platform. Access to training and materials require registration by the patients.

The program development is led by medical affairs who involve primarily the marketing and compliance/legal department plus some selected physician advisors who have been supportive during clinical development of the new drug.

The company decides to promote the program with prescribing physicians through their sales force. Supporting physicians would then suggest their patients to be called by an external agency thereby staying anonymous to the company. Patients interested would register and be trained by the external agency.

Educational telephone trainings would take 20 minutes on average. The company decides to make a difference between two groups of patients for the training once a patient has registered:

- High access barriers and low motivation to adhere with drug treatment: high frequency of educational calls through agency

- Low access barriers and high motivation to adhere with drug treatment: low frequency of educational calls through agency

Soon after first launch of the new drug the company learns that only few physicians promote the program with their patients. Among those patients who show an interest, only few finally register for the program. Among those few who register, the majority drops out from the program after awhile. On social media, the program is being discussed very critically and most comments discourage patients from registering. Feedback from physicians and patients alike focuses on “In principle a good idea, however: too time consuming; not what I really need; no solution for my issues; why do I have to register to get access to information?”, etc.

Last but not least the impact of the program on the actual treatment adherence of those patients who stayed with the program remains unknown as there was no measurement provided for.

The program is stopped prior to the original term planned.

Evaluation

What went well

In anticipation of challenges for patients to cope with the new treatment the company started to think about a patient support program (PSP) before launch. Many PSPs are only being developed once the product is already in the market and problems are being observed. Also, the company made sure that patient information remains anonymous to the company, thereby significantly decreasing the likelihood of issues with data protection and mistrust in regard of potential data misuse.

What can be improved?

The company had apparently missed to correctly analyze the potential issues patients may deal with and provide a solution that fits the needs and other priorities of patients in their daily life. Time needed for the program seems to too demanding. Overall the program design lacked the patient perspective and adaptation of the program features to the actual needs of the individual patient. The individual therapeutic objective was not part of the program, nor was the patient profiling individual enough for a proper determination of which kind of support was needed and useful. E.g. many patients may have welcomed access to printed or online educational material to try on their own first before registering for more or less telephone training. Peer-to peer communication among patients had not been taken into account.

As the focus was on education only the program did not provide for any solution in case of issues with the treatment that require intervention.

Last but not least physicians apparently did not agree or understand the benefit of the PSP for their patients or didn’t consider the benefit strong enough to dedicate time for introductions to their patients.

Considerations and recommendations

1. Involve patients early and understand their real need for support:

Keep in mind that a chronic patient usually has multiple issues to deal with. Pharmaceutical treatment is only one of them and then there might be a number of them. How does a Patient Support Program for only one of these issues fit the daily needs and challenges of the individual patient?

Source: admedicum® Business for Patients

Possible questions to be addressed by a treatment related PSP:

- What is the major issue with the treatment for the patient?

- How big is that issue relative to all other issues of the patient?

- How can a PSP help and what is the effect on the other issues?

- Can the PSP possibly be designed to improve several issues?

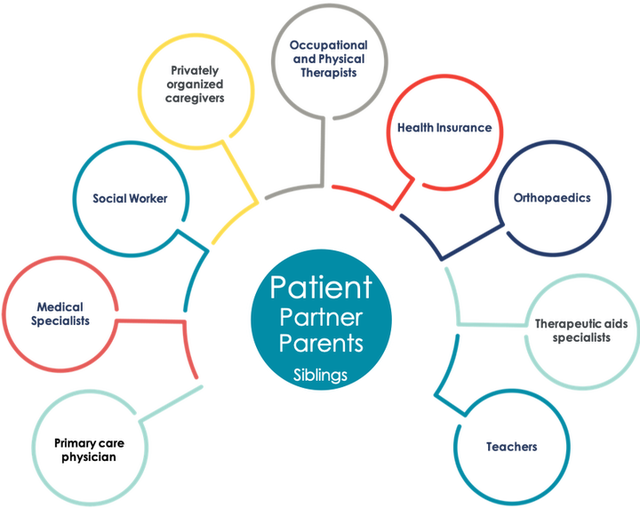

Another important aspect to be considered is that a chronic patient in particular in most cases is not alone but supported by family, a partner, friends or other personal caregivers. These people are affected too and a PSP may have an impact, good or bad, on their support for the patient. They may have an important different or complementary view on the needs and challenges. Understand their role and involve them too! They are all “patients”!

2. Collaboration with prescribing physicians:

There is no good PSP without the support of the trusted physician of patients. Early involvement of specialized and general practitioners in the conceptual set up of PSPs along with affected patients is essential. We recommend to not only work with Key Opinion Leaders but also with representative physicians who see many patients on a regular basis. The following graph may give some inspirational ideas about what to take into consideration during the development phase for both the program and the dissemination strategy.

Source: admedicum, inspired by Patient View

Possible thoughts of a physician related to a PSP:

- Does the PSP interfere with the individual therapy goal for my patient or with my own medical care principles?

- What’s the benefit for my patient?

- …and what is in for me?

- Does this cost me time and how can I justify that?

- Does it affect my prescription budget?

- Any legal concerns (e.g. anti-bribery)?

Some benefits which could make a physician consider supporting a PSP apart from efficacious therapy and reduced side effects / increased tolerability:

- Time savings

- Simplification of treatment

- Avoiding hospitalization or referal to specialist

- Structural improvements like

- Interface-management

- Data access

- Communication

- Patient satisfaction

Partnering With Patients in the Development and Lifecycle of Medicines, THERAPEUTIC INNOVATION & REGULATORY SCIENCE, 2015 Nov; 49(6): 929–939

Defining patient centricity with patients for patients and caregivers: a collaborative endeavor, BMJ Innovations, March 24, 2017

Help us improve this guidebook

Submit Feedback

Tool

Considerations for Implementing Expert Patient/Patient Group Input

Recommended Contributors :

- Program leaders

- Patient liaisons

- Sponsor representatives

- Clinical investigators

- Research team

- Trial site staff

- IRB

- Expert patient(s)/Patient Group representatives

Communicating with Patients throughout the Program

- How does the phase of drug/biologic/device development process covered by this program impact communication with patients?

- What translation and/or cultural adaptions?

- Wat language will be used to communicate with and about the patients?

- Are research questions and procedures culturally sensitive and appropriate?

- How will patients be referred to (e.g. “subject” vs. “patient” vs. “participant”)?

- What is the communication plan for patients throughout the program?

- Message content

- Audience

- Messenger

- Delivery mechanisms

- Timing

- Feedback mechanisms

- What feedback mechanisms and processes are in place for the patients to comment on sites, investigators, and the study participant experience?

- What role will social media play in the communications?

- How is social media defined?

- What restrictions should there be, if any?

- How can social media be used to advantage (e.g. for trial recruitment, to educate patients)?

- What limits should be placed on use of social media, if any? Why?

- How will those limits be communicated and enforced?

- What methods will be used to interact with patients and other stakeholders?

- Focus groups

- Interviews

- Surveys

- Inclusion on advisory councils

- Inclusion in meetings with researchers

- What data/information can and will be shared with the patients and when?

- Aggregate (de-identified)

- Patient-specific

- What are the restrictions (propieratry and regulatory) constraining the release of data?

- How do we ensure that this information is shared in patient-friendly language? How will that be determined/monitored?

Additional resources

Communication Handbook for Clinical Trials.

Guidance for Biomedical HIV Prevention Trials, p 37-38: “Stakeholder education plan.”

Checklist

Preparing a collaboration

Defining the interaction

Patients, patient representatives and industry should take responsibility to ensure interactions are meaningful by clearly defined processes and actions, progressed to timelines. In addition, all participants should be prepared for the interaction.

Prior to each interaction, agree mutually on (where applicable):

- The objective of project involving patients and/or areas of common interest to establish agreed structured interaction, providing all parties with necessary protection with regards to independence, privacy, confidentiality and expectations (see section 11. written agreement)

- The type of input and mandate of the involved person

- The tools and methods of interaction, e.g. types and frequency of meetings, ground rules, conflict resolution, evaluation

- Desired patient / patient partner organisation to foster long-term working partnerships, with independence ensured (in scope)

- The profile of the type of patient/s or patient representatives/s to be involved and their number

- How activity outputs will be used and ownership of outputs

- How and when the patient/s involved will be informed of outcomes

- Contractual terms and conditions including consent and compensation (see section 11, written agreement).

- Other elements according to the specific project

Source

Checklist

Preparing a collaboration

The four key principles for collaboration:

1. Clarity of Purpose

Each party should be clear about the reason for and the planned outcome of the collaboration – and the ultimate benefit for patients

2. Integrity

Each party should act and be seen to act honestly and with integrity at all times

3. Independence

Each party should maintain their independence

4. Transparency

Each party should be open and honest about the purpose of the collaboration and be able to account publicly for the associated activities and any exchanges of funding

Using this guide: a checklist

- Has there been a frank discussion about the purpose and expected benefits of the collaboration, and any risks, addressing all the issues in this guide?

- Are the objectives and planned outcomes of the collaboration specified?

- Are the roles of each partner and reporting mechanisms specified?

- Has a written agreement or contract been put in place, which sets out how each party will adhere to the four key principles?

- Is there a named senior individual accountable for managing and maintaining the relationship and monitoring adherence to the four key principles?

- Is information about the collaboration published on the company and charity websites?

- Can each party confidently explain the collaboration in public?

Source: National Voices, The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) (2015): Working

Checklist

Patient identification/interaction

Patient identification/interaction

There are many ways to identify patients to be involved in an interaction. The main routs are through:

- existing patient organisations

- EUPATI or similar project

- advertising opportunities for patient participation

- existing relationships with healthcare providers, hospitals and researchers and other agencies

- unsolicited requests previously made by interested parties

- existing advisory boards / groups (e.g. EFPIA Think Tank, Patients and Consumers Working Party at the EMA)

- this party agencies

Source: European Patients’Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI) (2016): Guidance for patient involvement for industry-led medicines R&D. (12/06/17)

Tool

List of useful conferences

Conferences with and for patients

Rare diseases conferences with and for patients

The Global Orphand Drug Conference and Expo

Indication specific conferences with and for patients

Tool

Defining role patients

Although you may not have selected the expert patients or patient groups (EP/PGs) yet, outlining their roles and responsibilities at this stage helps to define your needs. Keep in mind that EP/PG roles may vary at different of the program or may evolve in response to new requirements. Once selected, discuss the roles with your EP/PGs to clarify what they can contribute based on their unique expertise and experience and avoid misunderstandings at the outset, e.g., if they’re expecting to have a partnership role but you’ve designed reactor role (see Types of Patient Roles chart below).

| Patient Role | Examples | Engagement Level |

| Partnership role |

| High |

| Advisor role |

| Moderate |

| Reactor role |

| Low |

| Trial or study participant |

| None |

Source: DIA (2017): Considerations Guide to Implementing Patient-Centric Initiatives in Health Care Product

Development. (02/06/17)